Guns and Mental Health: The Ugly Truth

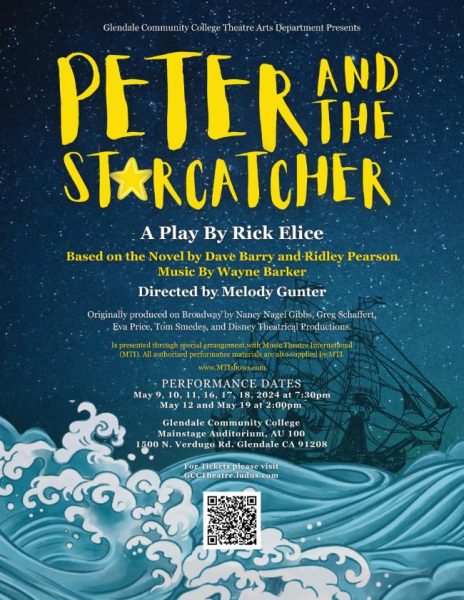

Societal concerns arise, as veteran kills 12 people in a Southern California bar

Ethan DeHoyos / Staff Photographer

Residents of Thousand Oaks and surrounding communities gathered to honor those who lost their lives in a mass shooting at a local bar.

Three hundred and twenty three — the total number of mass shootings this year. Three hundred and thirty-three — the number of days so far this year. A closer look paints a grim picture, as the statistics show an average of one mass shooting a day.

We as Americans, have become so immune to hearing about mass shootings that we have adapted a hopeless attitude when thinking about the possible resolution of this issue.

This time, one hit close to home. It forces our hand. We must have a difficult conversation that is often easier to ignore.

Just 36 miles northwest of Glendale sits Thousand Oaks — a city known for being among the safest in the country. In the recent weeks, however, the suburban town found itself in the ranks of places affected by a mass shooting in America.

It was a weekly tradition at the Borderline Bar and Grill to host “College Night,” where dozens of students from neighboring universities and colleges gathered for an evening of letting loose in a social environment marked by country music, beer, pool, and good times.

Some laughed, others danced. It was just a few weeks ahead of finals for these students and young patrons. The evening couldn’t get better. Up to the moment where a black-clad gunman opened fire in this jam-packed college bar on Nov. 7.

The bouncer was the first one down. Then it was the barman, a recent college graduate. Seconds later another shot was fired. Then another. And just like that, in the matter of 15 monstrous minutes, the crazed assassin left behind 150 bullets.

12 lives were lost. 13 people were injured. And those who did survive the gunshots, may never survive the trauma.

The shooter’s body was found in a bath of his own blood, in the back room of the bar. He had killed himself, too.

Ian David Long, the man accused of the mass killing, once attended California State University, Northridge. He was also a combat veteran of the Afghanistan war and a former machine gunner in the army. He had the experience to understand weapons. Potentially, moreover, he struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People noticed, but not a lot could be done. The combination of knowing about weapons and PTSD made him deadly.

The Back Story

On his block, Long was known as a man who was mostly quiet and reserved, but would have episodes of erratic behavior and mental breakdowns. His series of encounters with the police further proved the aforementioned.

Long’s mental health problems became especially visible last spring, as the troubled vet went through another nervous collapse. This suggested that he was dealing with something more than just anxiety, or mild depression. It was PTSD. He required professional care. Instead, the cops came.

The 28-year-old lived with his mother, who didn’t appear to do enough to force her son to get help. Interviews with neighbors suggested just that.

Richard Berge, a nearby resident, insinuated that Long’s mother was “frustrated that her son didn’t seek help for his condition.”

Someone like Long needed to have been pushed into help by those who loved him. He’s also a reflection of an argument made by the late Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer who argued in favor of bringing back well-managed institutions for those who need them and forcibly committing individuals. Right now, forcible commitment is difficult by law. When Long was evaluated by public officials, although they noted that he had issues, they didn’t have enough to force him to seek help. That’s a problem.

Do We Care Enough?

Although some veterans are able to move past trauma with minimal to no dysfunction in their lives, many continue to suffer the consequences of their previous circumstances.

Unfortunately, statistics show that the disruption of service members’ lives as a result of trauma symptoms is highly common.

Taking a deeper look into the symptoms of depression or PTSD, it becomes evident that the two have an awful lot in common. Some indications include social isolation and a lack of motivation. Both were characteristics of the ex-soldier’s latest days.

These mental conditions often result in social dysfunction, dissolution of marriage, significant substance use and sadly, crime and suicide. Earlier this year, the Department of Veterans Affairs reported that an average of 16.8 veterans commit suicide every day. This amounts to 6,132 veteran suicides each year. Such statistics raise serious concern and questions.

Has mental health taken a backseat in our society? And for those we purportedly care about and “thank” for their service?

While it is quite difficult to answer this question, one can surely assume that indeed, mental health still remains a taboo topic in everyday conversations. In addition, our society has grown out of tolerance mode and become too untrained to deal with those with mental issues, making them outcasts of the society. Perhaps this is when the animosity and self-destruction takes the wheel.

The Real Problem

While it’s easy to blame it all on the society, it is important to remember that every human is entitled to a sense of personal responsibility. It is up to the individual to want to get better—to get better.

The arguments are multifaceted and rather unfathomable, which in its turn receives endless counterarguments. Subsequently, the society is left exactly where it started—in a country of unsolved gun abuse, broken communities and split viewpoints.

We must take a deeper look into the mental health crisis in our country. Figures show that 43.8 million people deal with such illnesses in a given year, further proving that mental health is no longer a problem of an individual, but that of an entire nation. Be it social mores changing, a sense of fame that mass shooters are looking for, or something else, at the core is the mental health issue that we have neglected to our own detriment.

We could look at other aspects of better controls, like stricter background checks.

Perhaps it’s time to look at forcibly committing individuals like Long, who exhibit all the symptoms of potentially acting out in violent ways. Some might say that this could be detrimental to Constitutional rights, but, realistically, we have no other recourse, as these individuals break the law by the sheer fact they carry out mass shootings.

Growing up in a big family of journalists and writers, Marian developed her love for writing and reporting since early childhood. She is often found in...