The Anti-Social Network

What if I told you that you were in the midst of a great human experiment, where the goals of those running the experiment are well-defined, but the methods used and the potentially generation-defining consequences are unknown?

You likely wouldn’t believe it, but, in fact, you have already agreed to being a participant.

If you own a smartphone and use it to connect to the internet, you have effectively signed your name on the dotted line, voluntarily giving yourself up in exchange for being another data point in the experimenter’s worldwide trial.

You are the experiment, and you are the product. What these “researchers” – app designers, web developers, analytic services, broker companies and advertisers – are trying to learn more about is you. Your browsing habits on the internet, your social media use, the places you visit, who you talk to, and the products you search for, among other things, are all immensely valuable assets.

A study done by the Federal Trade Commission on nine prominent data brokers found that these companies earned roughly $426 million in revenue by selling customer data. This data is then used by advertisers to make personalized ads based on your browsing and buying tendencies, a highly-efficient means of getting products sold.

Have you ever wondered why social media platforms are so highly-valued? Facebook is valued at roughly $190 billion, Instagram at $35 billion, and Snapchat $40 billion. It’s because social media platforms – with their vast user bases totaling nearly three billion people – extract immense amounts of data, which are then sold off to the highest bidder.

With this much money at stake, each player in this information game has a colossal incentive to keep your eyeballs on the screen. The longer you are on your device, the more data that is extracted.

Knowing that time on screen equals money in the bank, designers of smartphones, apps, and websites tailor their products to be as addictive as possible.

Social media “feeds” are made to be attractive on the eyes, with their soft color schemes and sleek modern looks. Facebook and Instagram feeds are scrolling, which developers realize is the best way to keep you on-screen and searching through the application for something interesting. Snapchat has icons indicating “Snapstreaks,” where users are encouraged to not break their stretch of continuous messages with friends in a 24-hour window. App notifications are designed and colored to be attention-grabbing. The brightly-colored icons inform you of someone validating your opinion through a ‘like’ or ‘favorite,’ what psychologists refer to as social proof.

The validation attained through social media notifications, or the joy you get from checking new emails, scrolling through your news feed, and surfing from hyperlink to hyperlink scanning for that new tidbit of information, floods the brain with dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers.

This is the same compound released during enjoyable activities like sex, eating your favorite food, gambling, and drug use – which is why all of these things have the potential to be so highly addictive.

If you have trouble with obsessive smartphone use, it’s because your body has become accustomed to this flood of dopamine. In other words, you’re addicted.

Of course, an addiction only becomes an issue when the negative consequences nullify the positives. Americans are hopelessly addicted to caffeine, but the productivity boost received outweighs the restlessness, anxiety, and occasional heart palpitations.

The question now is: is our smartphone use – our addiction – having a noticeably negative effect on us?

Early results indicate that the answer is a resounding ‘yes.’

A 2016 National Institute on Drug Abuse study conducted on 8th-, 10th- and 12th-graders found that these age groups are going out with friends less often, going on fewer dates, having less sex, are more likely to experience periods of loneliness, and are less likely to get enough sleep than their predecessors. Additionally, since 2011, rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed.

Some of these trends hold true for college students, too. College students are spending less time socializing and more time browsing the distorted world of social media. Many experts think that prolonged use of social media has contributed to the increased levels of depression and anxiety among the 18- to 27-year-old demographic

It’s not just our mental health at stake, either. The way our brain functions is under an extensive renovation process, as well.

The idea that our brains are locked-in and fully developed when we reach adulthood is antiquated, and a semi-new theory of “neuroplasticity” has taken over the modern pedagogy of neuroscience.

The brain is constantly adapting to the stimulus applied to it; nerve cells “delete” old connections and form new ones, effectively altering the way it functions.

We are always plugged-in, surrounding ourselves in a world of constant distractions, which is molding us into distracted thinkers.

Many of you readers likely failed to make it this far in the article without thinking about, or indeed checking, your smartphone.

Instead of us having a sustained, linear thought-process, built up through prolonged reading or silent contemplation, where we are able to think deeply and almost meditatively about a topic in a flowing stream of consciousness, we are becoming shallow thinkers due to our propensity to desire information in scattered bits and pieces.

What the internet is doing now – in all of its distracting and procrastination-enabling abilities – is chipping away at the way we think. Just like a sculptor chiseling away at a piece of marble in hopes of creating a statue out of artistic impression, the bombardment of notifications in the information age is chiseling away at our linear thinking capabilities. But unlike the sculptor, the smartphone-shaped chisel isn’t creating art, it’s destroying it.

Could we be getting ahead of ourselves by declaring the “end times” at the hands of the internet-equipped smartphone? Surely. Many in Academia sounded the same alarms when the printing press, radio and television were created. But, as we have seen, these inventions brought about more good to society than they did bad.

We now live in an age where the ability to search for and take-in new information at breakneck speed is desired. Is this rewiring of our brains making us more adept for the society that we are trending towards? Is the increase in anxiety, depression, and suicide among our youth – which is correlated with extensive internet usage – just a statistical anomaly that will work itself out as we become accustomed to the changing times?

There’s not enough information to make a definitive claim.

What we do know at the moment, is that we are in the midst of a great human experiment. Should we be welcoming of this new age? Maybe.

For now, it might be time to disconnect.

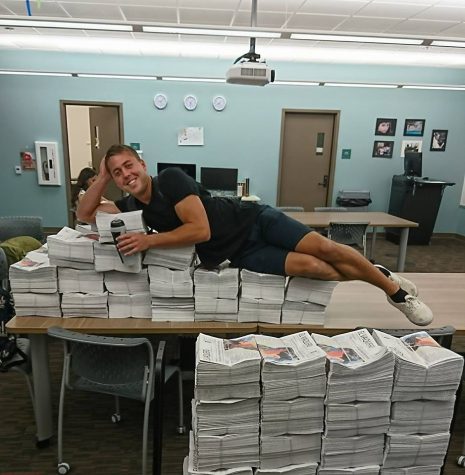

Ken Allard is a Los Angeles native and is in his fourth year at Glendale Community College. He enjoys covering hard news, politics, feature stories, sports,...