Solutions to Police Brutality Must Begin with Important Conversations

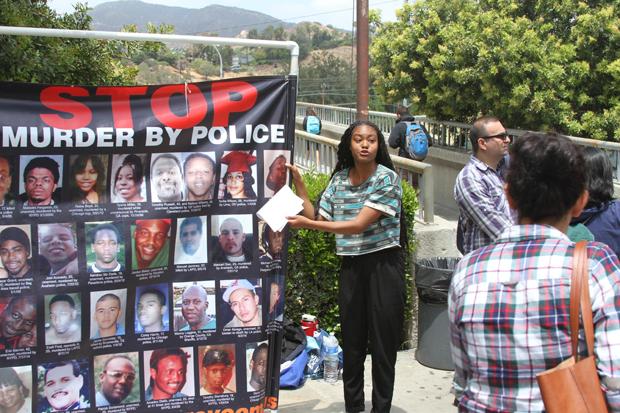

STOP THE MURDER: Breona Vaughn holds a banner depicting minority killings by police nationwide during a Black Lives Matter protest on campus in March, 2015. The list has grown far longer in the eight months since.

Eric Garner, 43, died as a result from a chokehold by police in July 2014 for selling cigarettes on the sidewalk in Staten Island, N.Y., setting off a wave of protests.

A month later, Michael Brown, 18, was shot by an officer in Ferguson, Miss., and a grand jury’s decision not to indict the officer sparked riots leaving local businesses in shambles.

Tamir Rice, 12, killed by police in Cleveland, Ohio, while playing with a toy pistol. Walter Scott, 50, was shot and killed while running away from a police officer during a routine traffic stop in Charleston, S.C.

Freddie Gray, 25, died while in police custody in Baltimore, Md. Sandra Bland, 28, was illegally detained in Waller County, Texas, and died in jail three days later.

Phillando Castile, 32, was shot to death at a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minn., with his girlfriend and her four-year-old in the backseat.

Keith Lamont Scott, 43, killed by police. Terence Crutcher, 40, killed by police.

The list goes on.

Charges against some of the officers involved in the killings ranged from manslaughter to murder, but others were only placed on administrative leave. We’ve come to expect a pattern: intense media coverage, community hysteria, the victim’s past brought to light, sides taken, protests, counter protests, riots, a Department of Justice investigation. Then it falls into the back of our minds until a few months, or weeks, or days later when it happens again.

But it always happens again.

Poverty stricken neighborhoods depleted of resources find themselves feeling defenseless, scrambling to defy the discrimination. Peaceful protesters flee to the streets but become exhausted after discovering the media focusing mostly on agitators in the crowd and their voices fall yet again on a sea of deaf ears.

According to The Counted, thus far in 2016, 827 civilians have been killed by police. 2015 held the highest number of police shootings in a over a decade. Thirty-five percent of unarmed people killed were African- American, despite them being only 13 percent of the population.

As a caucasian woman, I realize I don’t have the same daily anxieties as my African-American peers. I don’t fear for my life if I’m pulled over in my car or worry if my clothing will increase my chances of being stopped by police. This is due to my privilege, a shameful fact but a fact nonetheless. By acknowledging my own entitlement, the doors to honest conversations open.

Growing up in the South in the ’90s didn’t mean I was removed from the intolerant culture that pretended to be swept under the rug after the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation 40 years prior. It was still present. The bigotry crept in different ways though, maybe without the same transparency as before but as cultural tradition or patriotism.

Although, I’d like to believe that the South has grown away from it, never to look back or relish in its haunted past of public lynchings or the Klu Klux Klan, a few childhood experiences refuse to leave my memory: Confederate flags, representing the South’s fight in the Civil War to preserve slavery, hanging starkly on a friend’s living room wall while I join them for a wholesome family dinner or waving proudly on the back of a lifted truck in the lane next to me, racial slurs among grade school friends then laughter, de facto segregation in public schools and suburban neighborhoods. That was what my immediate environment exposed me to.

To neglect in identifying what I now understand to be racism, micro-aggressions or stereotyping would be not only morally wrong but a disservice to those who have taught me otherwise in my lifetime such as family, teachers, friends and colleagues. Life experience also has a funny way of humbling you, making you empathetic to things you wouldn’t think twice about before.

Presidential nominee Hillary Clinton referred to it as “implicit bias.” She proposed retraining police and addressing mental health concerns in the US. It shouldn’t go without saying

I have the utmost respect for police who go out every day to risk their lives to protect and serve their community with the best intentions. They recognize the deep-seated issues and do their best everyday to counter that. But our existing conditions just aren’t working for them or us.

“Police are overburdened,” said Ziza Delgado, a professor of history and ethnic studies. “They are sent to scenes where they’re dealing with homelessness, drug abuse, mental illness. These are scenes that should actually be dealt with by social workers, mental health experts, teachers and community members. If police are really there to protect and serve, they need to be completely retrained.” Efforts have begun to be made to address excessive use of force by police.

The US Department of Justice offers grants for law enforcement agencies interested in adopting community policing. Las Vegas and Chicago police department’s set up civilian review boards for independent investigations of complaints made against officers. Politicians offers solutions such as police training and gun control.

“I hope what comes out of all of these horrific and premature deaths is a very serious policy discussion, an urgent desire to change the system. Because it’s unsustainable,” said Delgado.

A study by American Sociological Report found that African-Americans were less likely, by the thousands, to dial 911 immediately following a highly publicized assault or death of a black person at the hands of police.

“Whether we call on them because of a dispute between neighbors or a robbery or a shooting or sexual violence, the police rarely meet our needs,” wrote Rose City Copwatch, a group in Portland, Ore. which promoted policing alternatives and restorative justice.

“Rather than serve as advocates for true justice they use their incredible power to reinforce the oppressive status-quo. They threaten us with violence and incarceration and target the most oppressed and vulnerable people in society. This is the current state of policing and it will be the future unless we work to change it.”

Rose City Copwatch disbanded in 2012, but other movements like Black Lives Matter and The Civil Rights Project at UCLA have taken their place.

Solving racial injustice is a web of complexity with no simple remedy. But to begin, we must have the uncomfortable but necessary conversations regarding our past that is ever-so-present in our culture today.

The shock and finality of repeatedly witnessing a person dying an unnecessary death as you simply scroll through your newsfeed can take its toll. What was once a sharp, unignorable pain becomes a dull ache and then numbness.

One is faced with a choice: to live in a perpetual state of helplessness, cursing the unfairness of it all, or to use one’s voice, refuse to become numb, to be empathetic with an open mind, to stand in solidarity with the victims, to have uncomfortable conversations so this never, ever has to happen again.

I choose the latter.

Morgan Stephens is a second year student at Glendale Community College. She was born and raised in Charlotte, North Carolina. After acting in Los Angeles...

Sal Polcino is a professional jazz guitarist and published songwriter. Since coming to Glendale College he has been published in the Glendale News-Press...