Tenacity and Truth Telling

ABC News’ exclusive interview featuring Caitlan Coleman Boyle, 31, from Stewartstown, Pa., raised a lot of questions and also laid some to rest regarding the experiences of the young American woman held captive for five years. Boyle was kidnapped along with her husband, Joshua Boyle, 34, of Perth-Andover, Canada, and had three children in Haqqani Network captivity. The group is part of the Taliban. The American arguably endured worse conditions than her husband. She allegedly had undergone a forced abortion and was raped multiple times by Taliban members. Her husband, for murky reasons, took her to Afghanistan with him in October 2012.

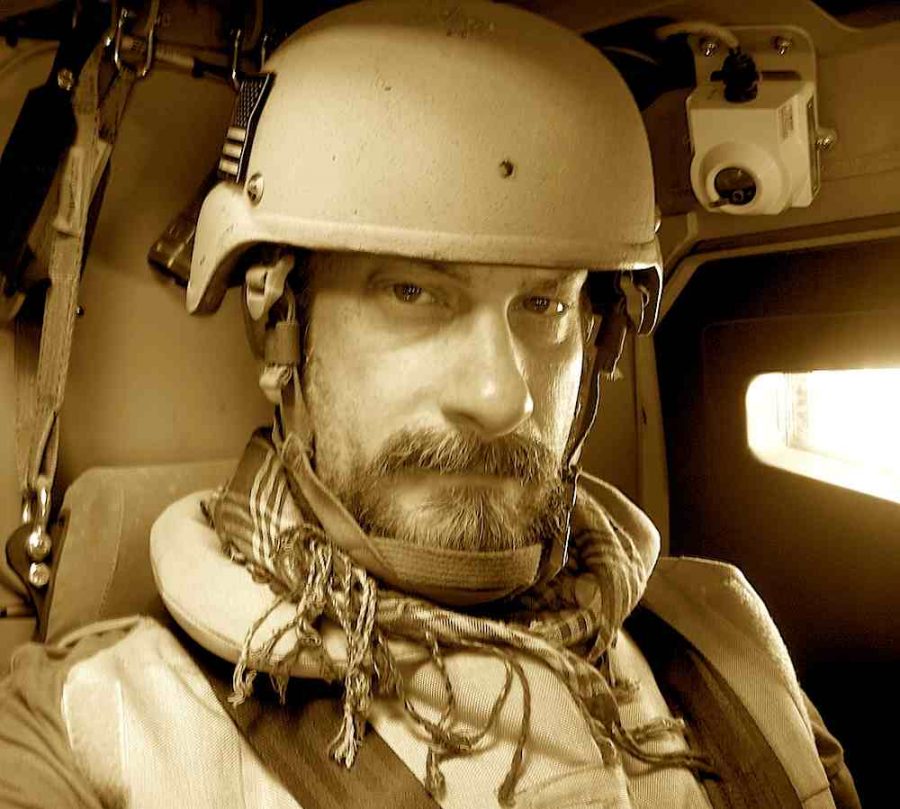

James Gordon Meek, the award-winning ABC producer, and his colleagues, including U.K. documentary filmmaker Sean Langan, spent countless hours to bring the ABC story to reality. For a journalist, that means developing a rapport that allows a source to feel unjudged and safe to speak.

Meek, who has won two awards from the Society of Professional Journalists for his reporting, is tenacious, as made evident from his reporting in the United States and abroad. He recently spoke at GCC’s Journalism Day, an event spearheaded by the school’s journalism department and students involved with the newspaper.

Ahead of his talk to GCC students, Meek agreed to be interviewed by El Vaquero editors.

How long ago did your career start? How did it start?

I studied editorial illustration, photography and filmmaking at VCU and also took up writing in earnest. I had discovered at an early age the power of narrative fiction and nonfiction when it delves into emotionally difficult subjects such as war. I also enjoyed writing satire well into my 20s. Both my parents were writers and I learned early on to get used to having tough editors critiquing my writing – or, as one high school teacher referred to himself as the dissector of our papers: “The Great Red Pen In The Sky.”

Everybody needs an editor, preferably a good one who improves your copy and reporting and teaches you a thing or two about human nature rather than impedes your progression or your storytelling. I started publishing experimental art and humor ‘zines as early as grade school and in college, as well as writing pieces for local arts newspapers, and eventually producing the first interactive political blog in D.C. from 1995-2003. I jumped at every opportunity, recognizing that all experiences amounted to a gradual process of seasoning.

What school did you go to? What did you study? How did the college you went to affect your future as a journalist?

VCU was – and still is – one of the top art schools and I was in a competitive commercial art program. Transitioning from editorial illustrator and photography into investigative reporting wasn’t as big a leap as you might think. But perhaps more important than the classes and the school was the era and the surrounding environment, which became a creative muse and where I gained street smarts and empathy for all kinds of people who struggled in life. I was part of the punk scene in the gritty streets of Richmond in the late 80s and early 90s, then America’s “murder capital.” And that “punk aesthetic” became ingrained – being a nonconformist, putting things in the proper perspective between that which matters and that which does not, thinking outside the box, questioning authority and confronting bureaucracy and official narratives – and it still serves me as an investigative reporter. I have respectfully confronted politicians, military leaders and terrorists alike, and I think my punk/alternative background gave me the confidence and the moxie to do that because I learned to embrace taking risks and living close to the edge in my youth.

What does it mean to you to be a journalist?

For me, it’s about fearless accountability, about shining a light on injustice and righting wrongs, and about putting folks in the shoes of others to see how they live.

What does a day in

the life for you look like?

There is no typical day for me but usually it starts with coffee and reading headlines on social media. Because I do investigative work, a lot of my time is spent checking in with sources and schmoozing with them, practicing a patient ritual that sometimes takes years before a relationship results in reportable information. I do a fair amount of face-to-face meetings with sources in order to build and strengthen long-term relationships.

When a major story is breaking, I’m up before dawn to do any reporting needed before “Good Morning America” airs at 7 a.m. eastern and to review scripts for stories I’m involved with to ensure we are always as accurate as possible. I often will write an accompanying news story for ABC’s website to pop early in the morning and coincide with a TV report I have helped to produce. One objective is to break stories or advance a narrative that will also get picked up by other news media and on social media. When a major story such as a terrorist attack or mass shooting is unfolding, I juggle phone calls and messages with my sources via email, text and encrypted messaging apps. There is a constant stream of reading other media and researching investigative topics.

And drinking coffee. A lot of coffee.

What’s the best thing journalism has taught you?

One of the greatest lessons a life in journalism has imparted upon me is the value of keeping your word, because of the dividends paid throughout your life – not just in your work – by earning a reputation for integrity. Everyone is asked sooner or later to compromise their integrity and you can never surrender it wholesale. You should never ever compromise your byline (your name) or your integrity, because you carry both beyond this school or this job to the next job, up on the next marquee or your next stage in life. Once you have compromised your integrity and lost the trust of your peers or the public, hang up your trench coat and toss your press credential in the trash; you’ll never get back your honor or credibility.

Also, to really understand a subject, you have to maintain your objectivity and yet learn to put yourself in your subjects’ shoes. Eventually you may gain empathy, which is more valuable to a reporter than a pen.

What are some of the topics you enjoy reporting? Why?

I have covered rock and roll and politics and I loved both. But in the past decade terrorism and national security have dominated my reporting. (I also spent a few years as a senior counterterrorism adviser to a pair of congressional committee chairmen.)

As incredible as it may seem, in the past four years terrorism has become a more difficult subject to cover and maintain my own emotional health and morale. Man’s inhumanity to man finally met the smartphone in places such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, and exposure to the carnage and cruelty of warfare has increased exponentially in my work because it has become so easy to document and distribute globally. It is both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is being able to have a window on the battlefield; the drawbacks include lack of context and simple volume of cruelty and death imagery online.

What has kept me going in this “death beat” frankly has been finding those human stories in which I have been able to use my investigative assets to help a few people who have lost loved ones to the injustices of war find answers and accountability, and therefore to find peace. That has made reporting on the rest of the carnage almost bearable and has motivated me.

Tell us a little about the most important recognition you’ve had in your career. Why did it matter so much to you?

I didn’t go into journalism to win prizes and I’ve rarely applied for journalism awards contests. When I am helping to break a story and the media is chasing our scoop rather than us chasing one of theirs, in my opinion we’ve won the day. We have won the “prize” for reporting – but just for Tuesday. Beyond that, I have earned the affection and respect of some extraordinary people whose lives I’ve intruded upon, such as the fallen in war, or a survivor of a tragic fire or families of terrorists’ hostages. That’s better than any journalism prize or professional recognition to me.

What are some projects that you are working on right now?

I rarely discuss investigative work that isn’t ready for publication or broadcast. But suffice it to say terrorism, war, hostages and security are all ongoing subjects.

Is it hard to be a journalist today versus when

you started?

I think that the shrinking media marketplace and profession of paid investigative journalism has made doing this for a living incredibly challenging. Some have said President Trump has helped grow that side of the business again. If that is true, it is an indictment of news organizations who didn’t need the election of Mr. Trump as a reason to maintain investigative journalism essential to the public interest, and yet many newsrooms shut down and laid off investigative teams over the past decade.

In other words, the need was always there and beefing up or restarting investigative teams to prove the Trump administration is corrupt is itself an example of a corrupt bias in my opinion, because the need for public accountability and watchdogs is always there regardless of who is in power. ABC News to its credit has maintained a robust and aggressive team for two decades under Chief Investigative Correspondent Brian Ross and Executive Producer Rhonda Schwartz.

The other major difference for those of us covering national security is that the legal and professional risks to our sources in government have been elevated by stepped up federal leak investigations and prosecutions intruding on journalists doing their jobs and those who help us keep the government and institutions honest. The public interest hasn’t changed but transparency has become more and more clouded in government operations.

What’s one advice you’d give a future journalist?

Don’t expect to make any money being a newsperson. Expect to work 70-hour weeks for little pay. Don’t take up this profession because you “like to write,” you’ll just be getting in the way of those who have genuine passion for covering the events and the personalities of our times and want to better the lives of the downtrodden and powerless.

I used to work at a small but respected legal newspaper. The end of the year came and they informed the staff that nobody was going to get a raise or bonus because this profitable newspaper couldn’t afford it. Instead, in a tone-deaf move, managers gave staffers hoodies stamped with the masthead emblem and on the back was a quote by Mother Teresa: “Our life of poverty is as necessary as the work itself.”

The sentiment was true even if management’s gesture was tacky. To be a good reporter, you have to become a warrior monk.

Growing up in a big family of journalists and writers, Marian developed her love for writing and reporting since early childhood. She is often found in...