As Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali battled it out in “The Fight of the Century” on March 8, 1971 to a roaring crowd of onlookers, eight seemingly ordinary Americans broke into an FBI office in Media, Pa., stealing more than 1,000 documents with the goal of fighting for the preservation of civil liberties against a government agency that ran roughshod over them.

The 1971 burglars included William C. Davidon, the leader of the group, Robert Williamson, married couple John and Bonnie Raines, and Keith Forsyth. They were members of the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, an activist group that aimed to reveal surveillance and intimidation tactics conducted by the bureau, led by J. Edgar Hoover at the time, to induce paranoia among American citizens, particularly Vietnam war protestors and civil rights activists.

On Jan. 28, 2015, 44 years after the burglary, two of the thieves, the Raines, will visit Glendale College to discuss the events leading up to the break-in and the importance of dissent in a democracy.

Joining them will be Betty Medsger, the first journalist to report on the stolen documents when they were first released, and Johanna Hamilton, who directed the film “1971” about the historic night. The movie will be featured at 11 a.m. in the auditorium, followed by a lunch break and a possible book signing between 12:30 and 1:30 p.m., and a discussion panel. The film will also be screened at 7 p.m.

History Professor Marguerite Renner is organizing the event at Glendale College; however, the group will also be visiting Caltech and Loyola Marymount University.

Renner’s husband, Robert M. Nelson, initiated the California tour after writing a review on Medsger’s book and comparing the 1971 Media events to that of the National Security Agency leaks by Edward Snowden, a former NSA employee who released classified documents that exposed the U.S. government’s spying on citizens.

“The actions of what happened in Media, Pa. are profoundly relevant today because we have another case of a similar situation of someone [Snowden] who brought information forward about the government spying on the entire population,” Nelson said.

“Every phone call is monitored and that would not have been known had it not been for Snowden making that information public. So, again, we get ask ourselves this question of why, very occasionally, very apparently normal, reasonable people are forced to break the law in order to serve something that is even higher, which is that agencies of government are breaking our Constitution.”

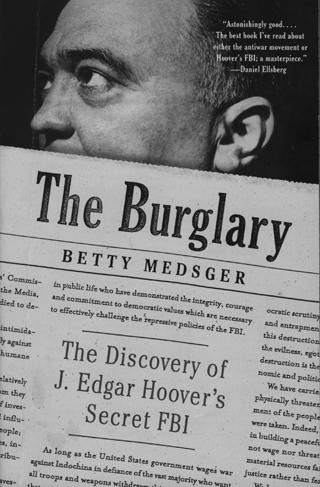

Despite a manhunt that ensued, with Hoover sending 200 agents to find the burglars, their identities remained unknown until earlier this year when Medsger published their names in her book “The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI.”

In her book, Medsger says the stolen documents revealed that there were two FBIs — one that the American public respected as their “protector from crime” and a secret FBI that aimed to silence dissent among activists whose values and opinions conflicted with Hoover’s, who reigned over the agency with an iron fist and encouraged the use of intimidation, “deception, disinformation and violence” against anti-war and civil rights activists.

“We really didn’t know what we would find,” said Bonnie. “But we had a pretty good hunch, since we knew the kind of intimidation and surveillance the FBI was doing in colleges all around the Philadelphia area.”

On the night of the break-in, Bonnie waited in a car on a side street next to the building so that if a police car came around, she could pretend she was having car trouble and block the police from going around to the front of the building, where four of the co-conspirators, disguised in sharp suits, were carrying out the burglary. Forsyth, whose day job was driving cabs, used a crowbar to get the door open.

John was waiting for them in a parking lot at Swarthmore College. Once the files were secured, they were transferred to his station wagon and he and Bonnie drove off together.

That same night, the burglars travelled to a farmhouse an hour outside of town, where they spent the next few weeks sorting out documents that they would send to news outlets.

What they found was “disturbing and incriminating,” Bonnie said, as their suspicions about the massive illegal surveillance and intimidation tactics were confirmed.

The burglary led to the discovery of COINTELPRO, a counter-intelligence program that targeted activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and aimed to disrupt groups that the FBI, particularly Hoover, deemed a threat to national security. The agency often used illegal surveillance.

Other targets included but were not limited to the Communist Party of the United States and the Black Panther Party. According to fbi.gov, however, all COINTELPRO operations ended in 1971, the same year the documents were released.

When Medsger first received the documents, she initially wondered if it was all just a hoax because the information within them seemed so extreme.

“Particularly the statement about creating paranoia and making people think that there was an FBI agent behind every mailbox,” she said. “It seemed like a pretty extreme thing, but it seemed even stranger that an agency would reduce that philosophy to paper and have it in its files.”

As Medsger read on, she found names of people she knew, which led her to believe that the files could actually be authentic. Once it was confirmed that they were real, she knew it was an important story that needed to be addressed. Although other news outlets turned the documents back over to the FBI, Medsger shared that information with the public.

At the time, she had been working at the Washington Post for just two years and felt “humbled” to have received the files, as there were more famous reporters the burglars could have sent the documents to. However, the Raines knew Medsger from Philadelphia, as she had written stories about John, a professor of religion at Temple University.

Medsger had also written about the protests against the war, so the burglars knew that she understood the antiwar movement and hoped that she would be in a position at the Washington Post to get the story out.

“I still marvel at the fact that people were able to do that,” Medsger said. “It has to do with a kind of courage that most us can’t even imagine….These were people of enormous courage and also people who were not egotistical and I think that has a lot to do with their success in this.”

The burglars never revealed their names or tried to take credit for the leaks, despite opening the American public’s eyes to the illegal actions of the FBI and helping lead up to the first Congressional investigation of intelligence agencies, including the FBI, the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency, in 1975.

“We agreed after the story got out that we would not meet again, ever,” Bonnie said. “We would not come together, ever, and we would not talk to anybody, even our immediate families, about it.”

Despite remaining acquainted with the Raines over the years that followed, Medsger had no idea that they were the Media burglars until 1989, when John accidentally blurted it out over dinner.

Medsger had been visiting old friends in Philadelphia at the time and was visiting the Raines at their house. When their youngest daughter, Mary, walked into the dining room, John said “Oh, Mary, we want you to meet Betty Medsger because she’s the person we sent the FBI files to at the Washington Post.”

Mary, who was not yet aware that her parents had broken into an FBI office all those years ago, did not really know what he was talking about, but according to Bonnie, Medsger’s mouth just dropped open and she practically fell off of her chair.

“That was exciting,” Medsger said. “When I received the documents [in 1971], I wasn’t jumping up and down. I was being a very careful reporter, sitting there and judging whether or not they were important or authentic. That was sobering, but all those years later, when I found out their secret, I couldn’t believe it.

“That was a sort of all-consuming, exciting moment that stayed with me for quite a while, until a few weeks later when I got in touch with them and said ‘I want to write a book and I hope you reconsider taking the secret to the grave.”

Medsger felt it was important to tell their story, as they were ordinary Americans, among them professors, cab drivers, and parents, with everything to lose when they broke into the FBI office for the sake of dissent.

The Raines had three children under the age of 10 when Davidon first asked them to be part of his plan to break into the office. They were the only parents in the Citizens’ Commission, so they contemplated over the risks of getting caught and sent to federal prison very seriously. However, Davidon was highly regarded and respected in the peace movement, which made the idea of the break-in seem less insane.

“He was a very smart and strategic guy,” Bonnie said. “If someone else in the movement other than Bill Davidon had suggested it, we might have just dismissed it and said ‘no, that’s crazy.’”

Ultimately, their faith in Davidon and their dedication to the peace and civil rights movements made their decision for them.

“We knew what kinds of threats were taking place, threats to our democracy and threats to our First Amendment rights,” Bonnie said. “The FBI was systematically trying to prevent and squash dissent and it was our constitutional right to oppose the war in Vietnam. He [Hoover] used his FBI to try to shut that all down…and so we just felt that as citizens in a democracy, we had do to bring a stop to that.”

With the statute of limitations expired, the burglars cannot be tried for the break-in, much to the dismay of Patrick Kelly, a retired FBI agent who investigated the burglary. Kelly told NBC News in January that the theft is still inexcusable, as “they are rationalizing a criminal act” and did not have the right to “take it upon themselves” to make that decision.

However, with the aftermath of 9/11 and the resulting NSA surveillance programs and Snowden scandal, the burglars’ actions serve as a reminder of the role of whistleblowers in society and the importance of citizen involvement in making sure that government agencies do not infringe upon civil liberties.

Bonnie said that whistleblowers are necessary in a democracy so that they can get the truth out, even at their own personal expense, a price she said that Snowden paid. , FBI, media pa.

“I think that you have a responsibility when you’re a citizen to make sure that the Constitution is not violated,” Bonnie said. “Citizens have to be the final ones who make that determination.”