Despite the advances made in social issues such as racism, sexism and environmentalism—the fight is far from over for many.

To inform students about social justice struggles both in the past and present, ethnic studies instructor Fabiola Torres and sociology professor Richard Kamei invited guest speakers from four different civil rights activist groups to speak at a historical panel discussion in Kreider Hall on April 4.

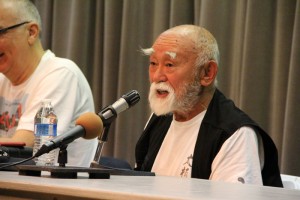

The guest speakers included Hank Jones, a former member of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, Carlos Montes, co-founder of the Brown Berets, a Chicano or Mexican-American civil rights organization, Mo Nishida, formerly of Asian Hardcore and currently an activist for the Jericho Movement, and Tammy Blacklightning from the American Indian Movement and Idle No More, an environmental activist group.

According to Kamei, he and Torres wanted students to be aware of the conditions that led to the formation of the aforementioned civil rights groups and to understand that individuals who were involved in civil rights struggles decades ago “did not just disappear” but are still active today.

Born in northern Mississippi in what he called a strictly segregated town, Jones became an advocate for civil rights after the murder of Emmett Till, a black boy who was beaten and murdered at the age of 14 by members of the Ku Klux Klan after allegedly whistling at a white woman. The murder, which took place less than 100 miles from Jones’ own home town, also helped spur the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

After seeing photos of Till’s battered body while stationed in Japan at the age of 19, Jones said he felt compelled to do something about the injustice and cruelty towards blacks, who he said were treated like second-class citizens.

“We had been segregated even in the military, we had been segregated even in Japan, and from that point [Till’s murder] on we decided that we would not put up with that any longer,” Jones said. “We began to integrate everything around us and we had to fight for that, but when we were done, we were free to come and go wherever we chose.”

Jones began doing community organizing work to improve living conditions and circumstances for blacks, demanding equal access and opportunity, better education, and representatives from their communities; however, he said because the “one percent” did not want change and countered civil rights actions with “brutal, naked oppression,” blacks responded with resistance. He removed himself from “mainstream politics” and joined the Black Panther Party because he said no one was defending black communities, and so they were forced to do so themselves. He said the Black Panther Party would have been unnecessary had there been justice and equality for all.

With similar distaste for the one percent, Nishida grew up at a time when Japanese Americans and descendants were sent to concentration camps during World War II. He claimed to have no idea he was an American citizen until he left the concentration camps and joined the United States military.

Upon his return, he visited communities with different ethnic backgrounds to see the state of racism and oppression during the Civil Rights Movement, but was rejected by whites and told to look at the state of his own community. He said that even upon visiting Glendale, non-whites were hauled out of the city.

To battle oppression faced by Asian-Americans, he helped found Asian Hardcore, an activist group that identified with the Black Panther Party and tried turning youth away from a life of crime but disbanded in the 1970s. During the movement, blacks, Asians, and Latinos identified with the struggles they were all facing as non-white, immigrant groups.

Nishida says that by attending the event he hoped to clarify some of the lies and distortions about the civil rights actions taken during the Civil Rights Movement, including the Jericho Movement, an organization that strives to free alleged political prisoners in the United States, in which he is currently an activist.

He said that many students graduating from college won’t have a future due to lack of jobs and environmental problems, which urges him to keep active in the community, despite the one percent’s lack of efforts and responsibility for these issues.

Blacklightning, an environmental activist, believes in protecting nature for future generations. An Indian American, she grew up respecting Mother Earth but was also bullied for her ethnic background as a student, often harassed and called ugly for her distinctive Indian American features on her way home from school.

A lesbian, she is also active in supporting LGBT rights. She says her culture embraces homosexuals as individuals who have two spirits, and are thus attracted to both genders.

Diédre Diekmann, a history major who attended the panel, agrees with Nishida’s and the other panelists’ claims that people living in the United States are “oppressed by a system that encourages inequality and injustice.” Diekmann said that though society has come a long way with de jure issues in regards to social issues, de facto social justice issues including racism, sexism and homophobia have not.

Although Kreider Hall was filled with students for the discussion, Diekmann believes that there is a significant lack in youth awareness and involvement in social activism.

Similarly, Montes said that though there is some youth participation, there could be more; however, due to misinformation and lack of information on behalf of high school educators and media contributes to the lack of involvement. Attracted by the college’s diverse ethnic population, he attended with the goal of helping students learn what steps to take in regards to social activism and to encourage more involvement in their communities. He said he was happy and surprised to see that the auditorium was packed.

Like the previous activist groups, he founded the Brown Berets to advocate for equal opportunity, better education, and to fight against police brutality while also protesting the Vietnam War. In 2011, Montes was escorted of his home by two SWAT teams who broke down his door. A registered gun owner, Montes was previously convicted for throwing a soda can at a police officer during a demonstration in 1969. A sheriff explained that because convicted felons cannot own guns, it was cause to arrest Montes whose guns had been previously registered, according to The Guardian. Montes and his supporters said that he was a target due to his activism; however, the felony charges were dropped.