‘Enough Said’ Explains Political Word Games

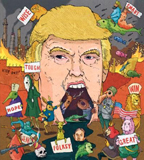

Illustration by Wesley Merritt

PARATAXIS: Donald Trump uses short sentences, repetition and catchphrases in campaign speeches to sway supporters. Believe me!

“If for I want that glib and oily art. To speak and purpose not.”

In Shakespeare’s “King Lear,” Lear’s daughter Cordelia says that she doesn’t have the skill to lie.

In Mark Thompson’s auspicious book, “Enough Said,” the author attempts to explain how that particular skill, the use of rhetoric to lie and deceive, is what has gone wrong with politics and the use of contemporary public language.

Thompson, president and CEO of the New York Times Co. and former director-general of the BBC, is in a unique position to investigate this issue.

“Public language matters” is the opening statement in Thompson’s book. In this age of digital media, there is a virtual world where a politician can plant an idea that could reach 10 million minds before leaving the podium.

This phenomenon was witnessed Sunday evening during the presidential debates. Truth doesn’t matter, only words and how they are presented.

Thompson’s first example of media swaying public opinion is a statement made by former Lt. Gov. of New York, Betsy McCaughey, attempting to discredit the Affordable Care Act while on Fred Thompson’s radio show in 2009.

“Every five years, people in Medicare will have a required counseling session that will tell them how to end their life sooner,” McCaughey said.

This statement was completely untrue, yet began a negative campaign, which vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin perpetuated by using the epithet, “Death List.” These false and misleading statements influenced millions.

Uncompromising ideology permeates both political parties in the U.S., despite the fact that compromise is the key to successful government.

According to Thompson, there is low trust in politics. Conspiracy theories and anger abound. Donald Trump feeds on this anger.

“There is great anger. Believe me,” said Trump in a campaign speech in March.

Thompson compares Trump to Hitler in that they both believe that if language sounds authentic, then it is authentic.

The anger extends to individuals as well. Thompson cites George W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, President Obama and now Hillary Clinton as shouldering the blame for many of society’s problems.

In 2007, British Prime Minister Tony Blair accused journalists of replacing responsible reporting with sensationalism and character assassination, making harder to find honest dialogue.

Thompson said the informed public is the elite and that truth, facts and science no longer have the privileged status they once held. The public and the journalists do not fully understand the issues. Politicians distort reality with jargon and doublespeak, deliberately ambiguous or euphemistic speech used to obscure or evade.

Political speeches are filled with catchphrases and slogans. Trump uses parataxis, which are short sentences and repeated words like “believe me.”

“Trump has found a wanton ecstasy in it, a joyous spasm of indignation in which his supporters are only too happy to lose themselves.” Thompson points out that Trump adapts to the mood of his audience with “great skill.” Another rhetorical trick that Trump takes advantage of is alliteration. Like Caesar’s “veni vidi vici,” the candidate uses phrases like “walls work.”

Thompson writes of his own role in journalistic integrity. In 1986, after the U.S. bombing of Libya, he felt that the reporting was whitewashed and sensationalistic. BBC was behind in its reporting of daily news, so he produced a late news segment to present more timely news, striving to compete with the following morning’s newspapers. Crucial stories were presented in a nine 9 o’clock broadcast.

The author cites George Orwell from his 1946 essay “Politics in the English Language,” in which Orwell advises against clichés and other pitfalls and misuse of public language, such as “the unnecessary use of long words, over-writing, excessive use of the passive voice and pretentious foreign or technical terms.” Thompson thinks politicians have ignored that advice.

The author feels that the legacy of honest and in-depth reporting has been destroyed by the internet. Because of the “instant news” presented in posts, tweets and memes millions of people get their news in abbreviated form and many don’t even read the full story, but just the click-bait headline.

According to Thompson, politics has become marketing. The first 10 words of a story cause readers to form snap judgments, very much like advertising. Nancy Duarte, in her book, “HBR Guide to Persuasive Presentation,” says, “We live in a first draft culture. Compose an email. Send. Write a blog. Post. Why care about being an excellent communicator when you have so many other pressing things to do.”

After reading “Enough Said,” one will not come away with any real solution to the dumbing down of language in politics. The author believes it would take a global catastrophe to cauterize public language, like a third world war.

The principles of rhetoric, ethos, pathos and logos, now lean mostly to pathos—pity and sadness. Yet the author tells us, “Don’t despair. Public language has come back before. Just open your ears, use good judgment, think, speak and laugh. Cut through the noise.” Not very encouraging.

Sal Polcino is a professional jazz guitarist and published songwriter. Since coming to Glendale College he has been published in the Glendale News-Press...