Californian author and essayist D.J. Waldie spoke to a full audience in Kreider Hall Oct. 19 on his book, “Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir” and on his life in Lakewood in the 1950s.

“My story is very much about the experience of growing up for tens of thousands of Angelenos who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s, who grew up in the little houses on little lots like those in Lakewood,” said Waldie. “This book, though quite specific in terms of characterization of a particular place, is really about a lot of different places.”

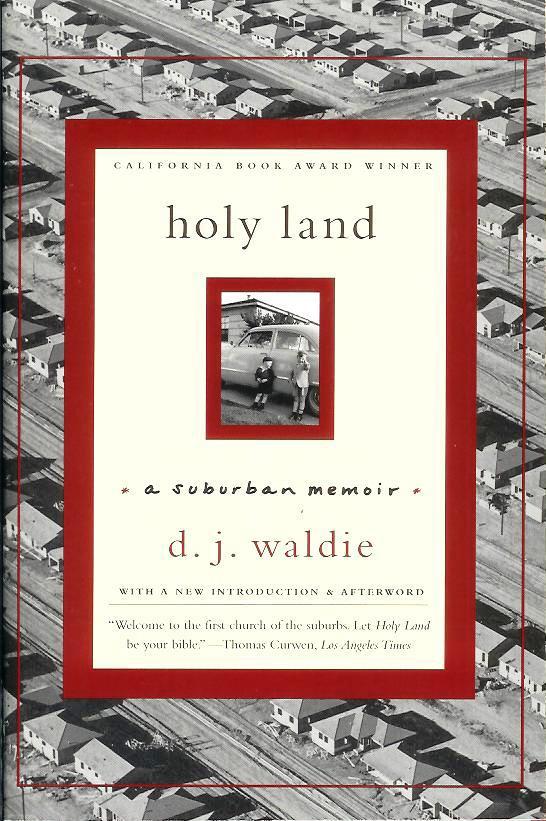

“Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir” is an autobiography written in 2005 composed of sections — 316 in total — describing the day-to-day accounts and aspects of living in post World War II suburbia.

According to Waldie, all portions are a “typewritten page” of around 250 words and at least a sentence in length. Sections are divided by loose associations, ranging from anecdotes about his life to the logistics of Lakewood.

“‘Holy Land’ began as collection of bits; it was always in the form of bits,” said Waldie. “The bits stand alone like a little house, a little lot on the gridded street — [they’re] all connected to each other by the common fate they share.”

“Holy Land” has more than Waldie’s personal anecdotes on life in a suburban area. It includes facts and figures on the construction, development, and economy of Lakewood and the areas near it.

Composed of Waldie’s bits, suburban data and photos taken of Lakewood and the surrounding area, Waldie composes an argument for the merits of suburbia as opposed to the ideas that areas like Lakewood lack culture.

“I bring all of that into the story because I believe that deepens the implications,” said Waldie. “When we talk about who we are in a place and we don’t know enough about the physical realities of the landscape, we lack something in our knowledge. In other words, place-mindedness — becoming sensitive to the meaning of place — includes the seemingly insignificant details of landscape, water production, land use history, all of that.”

Waldie began his reading with “12,” an account of the developers of Lakewood asking the photographer William A. Garnett to take a series of aerial photos of the progress of the suburbs’ construction.

Waldie continued to read excerpts from “Holy Land,” including a story of a man dubbed as “Mr. H,” the neighborhood compulsive hoarder who collected broken appliances and strewed them on his lawn, the discovery of his dead father in the home’s bathroom (resulting from tachycardia, or excessive beating of the heart), and the death of an Episcopalian family’s baby and how his mother baptized the body to console the mother.

Other, more lighter topics included the display of childrens’ models of Calishopping center and the constant rate of construction of the suburbs after WWII.

Waldie finished his reading with the final week of Lent at Lakewood — entries “313,” through “316.”

“313,” an account of the ceremonies of Holy Thursday, particularly the washing of the feet of the Lakewood residents and the awkwardness that that brought to both the men of Lakewood and the priests.

“315” speaks about his participation of the veneration of the cross, and how the members of the church would go to the figure of Jesus and kiss the figure’s face.

“They came forward. . . and kissed the feet of the figure of Jesus on the cross. If I was holding the cross I tried to keep it as steady as possible. If I was holding the square of starched white cloth, I was supposed to wipe the feet of the figure. I wasn’t sure if this was reverence or something that had to do with hygiene. The cloth I carried grew bright red from the lipstick I wiped from the feet of Jesus.”

“316,” speaks of the Latin verses spoken at the ceremonies, particularly Pange Lingua, a traditional Good Friday hymn.

“Sweet the wood. Sweet the nail. Sweet the weight you bear,” were the final words of his reading.

During the question and answer session, Waldie addressed the common stereotype of the “meaning-free, soulless, dehumanizing” suburb.

“It has been a common trope in American cultural criticism to regard mass-produced, post-war suburbs as [writer] James Howard Kunstler describes it. . . the place where evil dwells. I do not subscribe to Kunstler’s view,” said Waldie.

Waldie also commented on how the lifestyle that once existed during his childhood was vanishing today.

“The place I describe in ‘Holy Land’ seems to be a disappearing option for many young people and older,” said Waldie. “The better life that my parents found in Lakewood and the better life that their working class neighbors, men and women who worked with their hands manufacturing all the good things in life — that good life is shifting away. I suspect that you should consider strongly how this country can modify its present political and economic structures to provide more of that good life that I had as a child.”

“Do you ever feel your father’s or mother’s spiritual energy?” an audience member asked.

“Oh, not in the way that you might be suggesting,” said Waldie. “But they end up in my prayers every day, so I suppose I might conjure them up every morning as I walk to work.”

Ultimately, the book focuses on locations and the effect that they have on people, said Waldie.

“Even though your life experience may be radically different, this book might have you think about how your place has influenced your life,” said Waldie, “what marks the place from you come has placed on your soul, on your heart.”

Waldie hopes that readers are inspired by his book’s format of bits and apply it to their own lives.

“[The different bits’ connections have] a quality that is material, it’s a real connection but it also has a lyrical, a poetic quality,” said Waldie. “So I’m suggesting when you walk out of this room and see the different bits of your life, you might compose a poem out of it.”

“Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir” can be found online at www.amazon.com.